Adventure Time!

I’m having neurosurgery one week from today. At 9am on July 17, I’ll check in at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia hospital, meet with the surgeon, and then be put under general anesthetic to have stents (the exact number of which will be determined on site) inserted in the dural sinus veins at the back of my head in a procedure creatively called ‘venous sinus stenting’ (VSS). If all goes well, I should be out of surgery and in recovery in the ICU by 1pm.

The rest of this post provides all the gory details of why I need the surgery and what it does - both for the delight of my fellow science-and/or-medical nerds and because I find it very comforting to work through exactly what’s going to happen and why. I realize that such things are not everyone’s cup of tea, though, so no offense if you want to take a pass! Neither my spouse nor my child, for instance, will read past this warning. (My father and I, on the other hand, have both watched multiple videos and read a number of medical articles on VSS as a form of self-soothing.)

For neurosurgery, this procedure is minimally invasive and low-risk. Rather than slicing my head open and drilling through my skull, the surgeon goes in through a small incision in my femoral artery and uses a super-fancy radiology set-up to guide a wire all the way from my groin up to the major veins at the back of my brain. As far as I’m concerned, this is a vast improvement over the two surgeries that used to be the standard for the kind of intracranial pressure issues I’m dealing with: 1) inserting permanent shunts to drain excess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) into the abdomen (*shudder*) and 2) optic nerve defenestration, where the surgeon slices the optic nerve(s) open to relieve the pressure from the built-up CSF (*double shudder* and it doesn’t even relieve the other symptoms of increased intracranial pressure). In happy contrast, “all” I’ll be left with at the end of the day are some flexible metal mesh tubes holding a vein/veins open.

It’s funny, in a way: I’ve felt this coming for almost two years now. When Andy and I met with my neurologist in October 2023 to discuss next steps after I’d been treated (twice) for meningoencephalitis and still had significant swelling of my optic nerves and high intracranial pressure, she recommended Diamox (a diuretic I spent a very unhappy six months on, although it did help the pressure), dieting, or even bariatric surgery to lose 12-15% of my body mass “because this has been shown to help in some cases” (this is worth a separate post of its own about how fat-phobia affects even otherwise really fantastic doctors: the cases in which this has been documented to help involve people who started experiencing symptoms shortly after gaining a great deal of weight, whereas my BMI, which hasn’t changed since 2016, doesn’t even qualify me as “obese”, much less reaching the recommended bariatric surgery cutoff score of 40 or higher). And then she mentioned that, in rare cases, it takes neurosurgery to alleviate the pressure.

Andy immediately looked over at me and said, “That’s going to be you.”

And now it is.

The pressure in my cranium was delightfully low post-lumbar-puncture and subsequent CSF leak in August 2024, and I had hoped that the drop in pressure would give the veins that were almost completely closed off the chance to re-open. Alas! The pressure took months to build back, but build back it did - and then when the VZV in my left eye re-exploded this spring, the pressure re-exploded too.

I’d been trying to grit my teeth and bear it until the surgery, but my neuropsychologist convinced me to tell my neurologist how awful I was feeling, and my neurologist got worried enough when she read my message that she personally called my neuro-ophthalmologist and scheduled a same-day appointment with her for me, and then a bunch of tests confirmed that I am currently all the way back to the level of brain-swollenness from October 2023, and so my neuro-ophthalmologist texted my neurologist to let her know (while I was still sitting in the office), and by the time Andy and I got back home, my neurologist had ordered me Diamox and prednisone and also talked to my neurosurgeon and gotten him to bump my procedure up to the 17th.

The point of that story is two-fold: first, my medical team is incredibly cooperative and awesome and I love them; second, the team contains a ridiculous number of doctors with ‘neuro’ prefixes.

Anyway! That’s not the fun stuff. The fun stuff = gruesome details and cool images. Here we go.

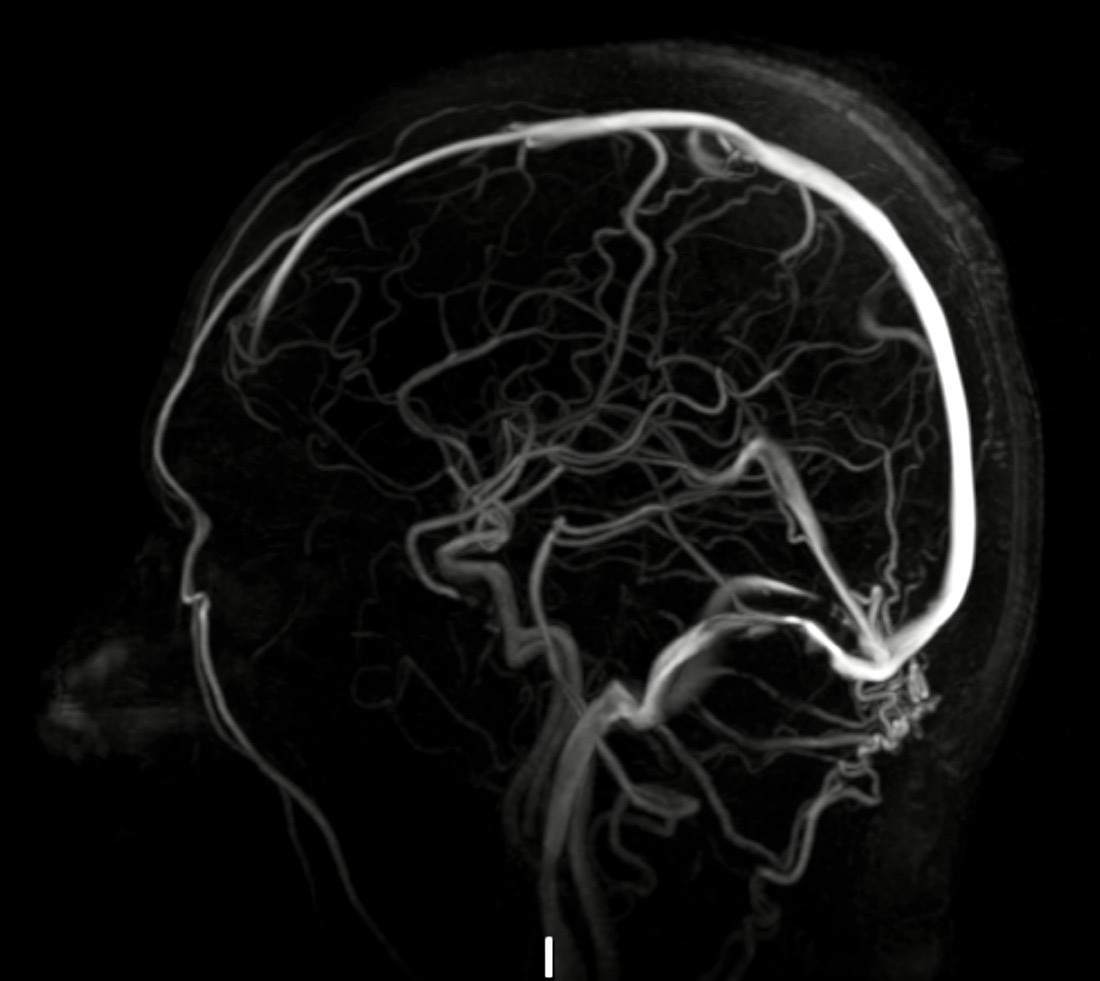

So! Your dural venous sinuses are basically large valveless veins that run through the ‘dura’ covering your brain. The ones that are messed up in my case are the transverse and sigmoid sinuses, which I’ve helpfully circled in orange here in this lovely stock photo:

See how thick and plump they look? That’s wonderful, because they are the veins most responsible for regulating your intracranial pressure by draining CSF and blood down your internal jugular veins. You want them to look like that.

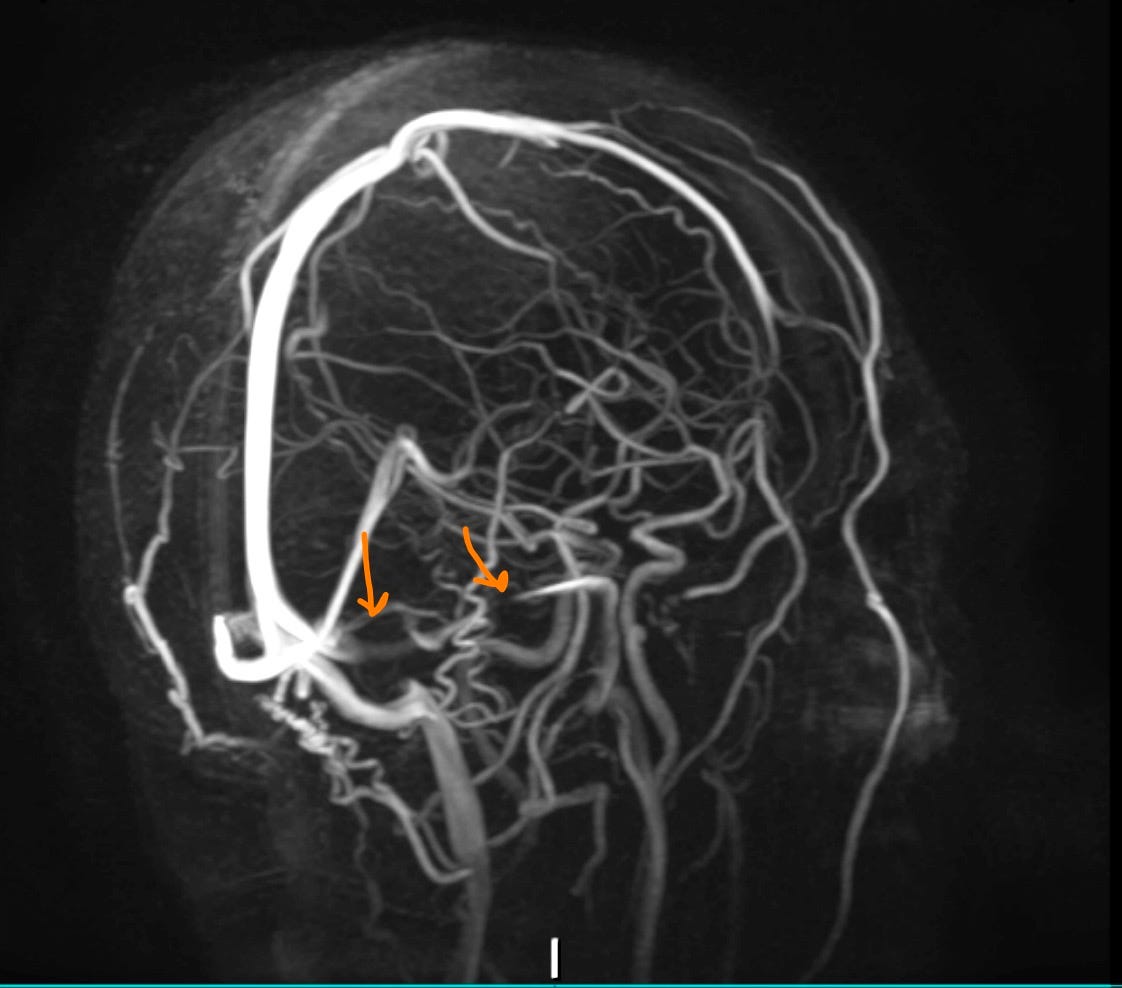

Here is a photo from the same angle of my most recent MRV back in April 2025 (which was before my intracranial pressure got really out of control again in June, so I don’t even want to know what it looks like now):

You may notice even without the helpful orange arrows I’ve added that this image doesn’t look *quite* like the stock photo. Here’s another angle:

You can see on the far left side that I’ve got some narrowing of the transverse sinus there, but mostly what you notice is that you can’t really see most of my right transverse and sigmoid sinus. I like to look at this and channel Michael Caine in the make-over scene from Miss Congeniality: “Dural transverse sinuses. There should be TWO!”

What on earth is happening here? Well, I’m glad you asked, because I’d spent ages thinking that my dural sinuses were getting squished from external pressure in my meninges and brain because what else would it be, and instead it turns out that there are two completely different sorts of stenosis you can have: extrinsic and intrinsic.

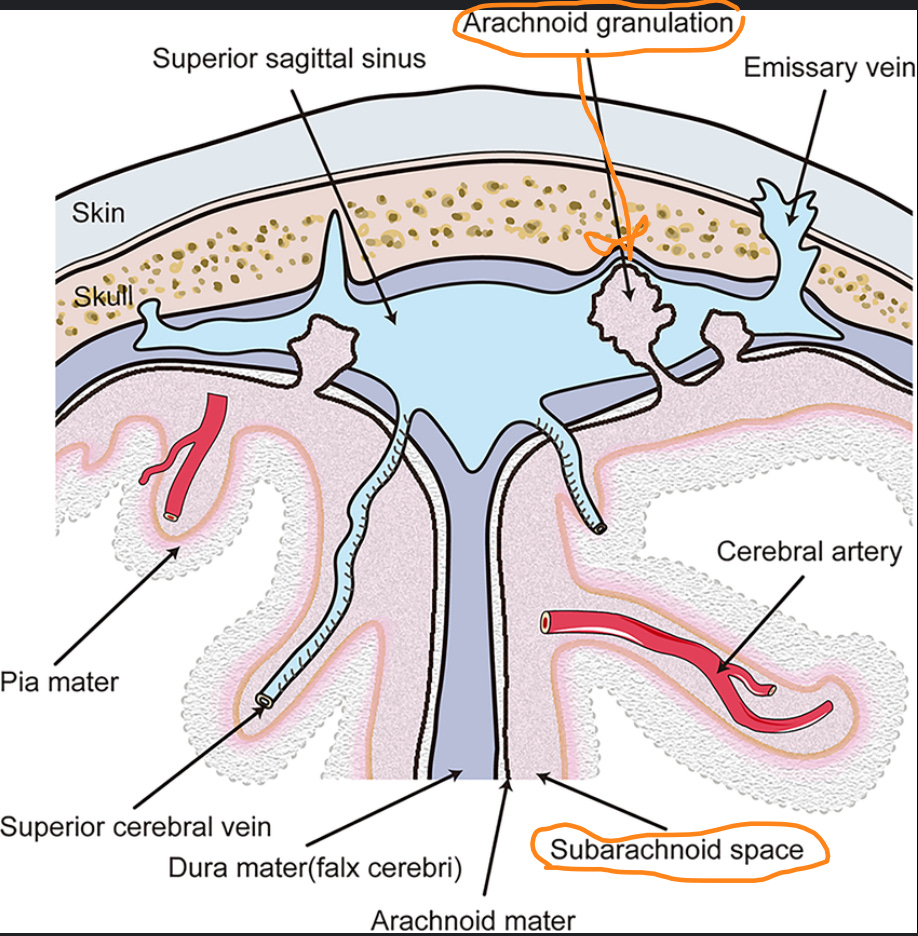

The most common type of dural venous stenosis is extrinsic - the kind I knew about - where there’s narrowing of the vein from external pressure or malformations pressing in. But there’s also a less common type called ‘intrinsic stenosis’, caused by something called - I kid you not - an ‘arachnoid granulation’ which has protruded from the subarachnoid space under the arachnoid layer of your meninges and into the dural venous sinuses in a way that obstructs blood flow. It’s normal to have small arachnoid granulations: they help drain CSF into the veins to regulate intracranial pressure. What you don’t want is for these arachnoid granulations to become “giant” or “significant” and start blocking the blood flow in your dural venous sinuses.

When David was visiting recently, I asked him which sort he thought I had - the more common extrinsic or rarer intrinsic, and he instantly responded: “Intrinsic, obviously!” Then he paused for a second and said, “Actually Mom, I’m going to say BOTH. That’s got to be the rarest kind, right?” And, as usual, my child was correct. The neurosurgeon’s notes describe “bilateral venous sinus narrowing with a significant arachnoid granulation on each side in the dominant right transverse sigmoid sinus.” So I’m two for two!

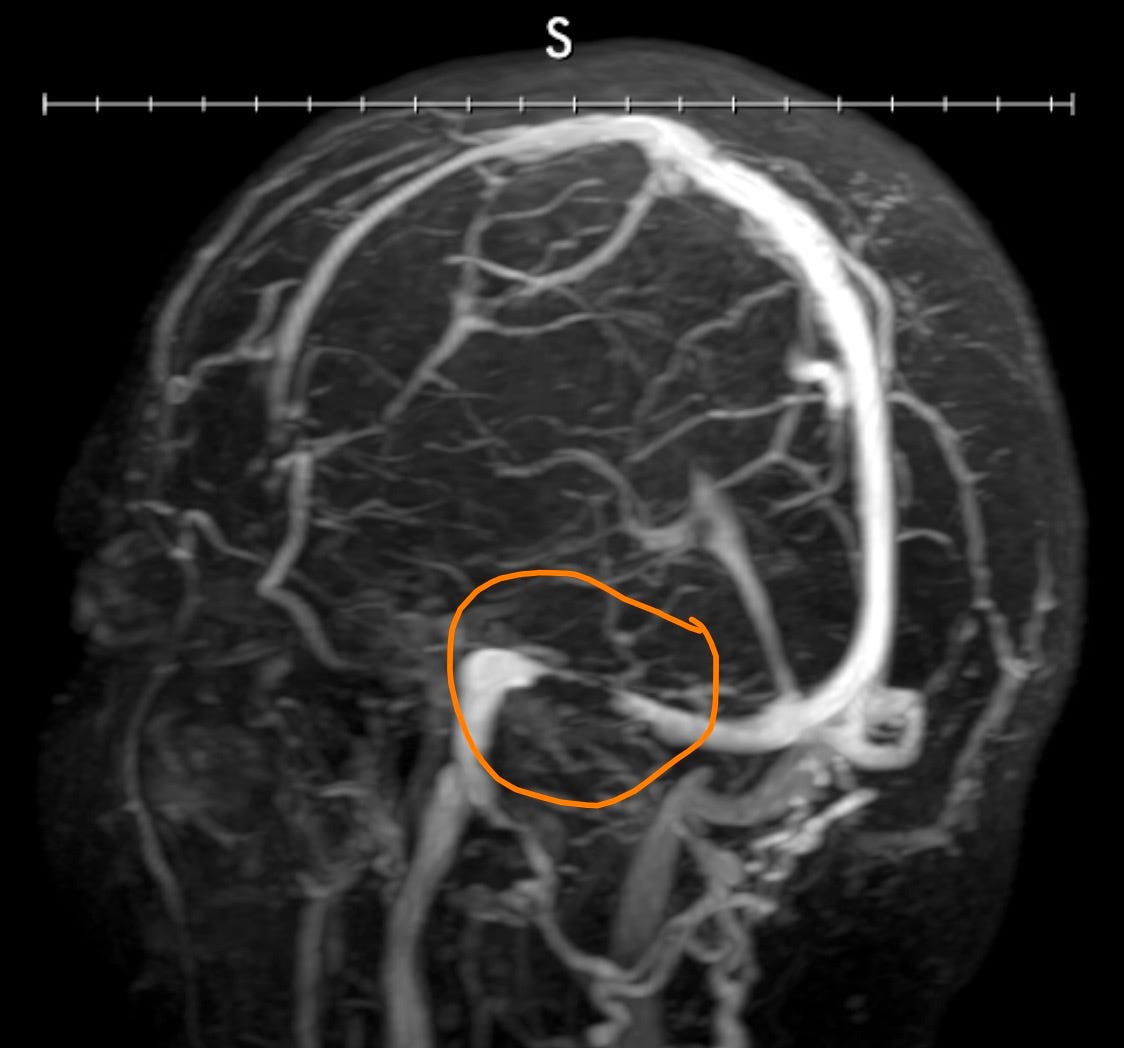

You can see one of the arachnoid granulations really clearly here, looking all black and ominous because it’s opaque on the sort of scan they were doing - it’s really just a squishy ball of CSF fluid:

Not surprisingly, this level of blockage (not to mention the other bits) is preventing my CSF from draining properly (a particular problem because of the recurring meningitis), which creates fun side effects like

constant ‘ice cream’ style headache that frequently wakes me up at night,

nerve pain in my neck and spine that also radiates down my arms and legs,

blurred and double vision

tinny, high-pitched whooshing in my ears like a DJ mixed a fetal heartbeat with some wicked microphone feedback and then forgot to drop the beat

nausea that comes and goes but mostly comes, and

fatigue like a thick, wet, hot blanket weighing down my limbs and thoughts

Not my favorite.

Fortunately, my neurosurgeon - who is so specialized that he “dedicates his practice exclusively to diseases associated with the cerebrovascular system” - is confident that the stenting will significantly improve my ‘quality of life’. And because this procedure involves my dural venous sinuses and not, say, my great cerebral vein, all medical equipment and exciting happenings should remain (more) safely on the surface of my brain instead of delving inside it.

The first step of the surgery is to run a catheter up from my femoral artery to my dural venous sinuses, and perform a “venous sinus manometry venography and angiography” to measure the pressure on each side of the areas of stenosis and to “rule out a fistula”. (I am not AT ALL excited about the prospect of them finding a dural arteriovenous fistula - dAVF - but at least fixing them is one of the things my surgeon specializes in?) Assuming all goes well with the venography and angiography, the next thing the doctor will do is place flexible mesh stents via another catheter wherever they’re most needed, and theoretically, my brain draining powers should start to increase immediately.

One interesting thing is that they’re only going to stent one side next week: that’s usually enough to alleviate the intracranial pressure and corresponding symptoms, and obviously it decreases the chances of surgical complications (which, even if rare, tend to involve alarming words like ‘hemorrhage” and “hematoma”). People generally have a dominant sinus, and mine is the one that’s mostly blocked off, so the hope is that opening it back up will be enough to do the trick. Dr. Levine says that he’s only had to go back two times in his entire career to do the other side. (Literally everyone I’ve mentioned this to: “You’re going to be the third.”)

There’s a really great video about the procedure here, in case you want to really geek out. Recent medical advancements in non-invasive surgery are amazing, and I’m incredibly grateful to have this particular surgery be an option.

Ok! Those are the basic nuts and bolts about what’s happening next week and why. I leave you with an image looking down at my brain (you can see my eyeballs on the top), because I love how there’s a little heart shape right there in the middle.

A heart in my head, just the way it should be.

Until next time, be nice to your noggins!!

May all be well and may the surgery do what you hope and expect, Christina! And, meantime,

you could always become a medical writer!

Traveling mercies on July 17 (for the catheters and stents as well.) Is that arachnoid granulation supposed to look like a fat spider? Would be appropriate.